The current COVID-19 pandemic and the accompanying ‘infodemic’ clearly illustrate that access to reliable information is crucial to coordinating a timely crisis response in democratic societies. Inaccurate information and the muzzling of important information sources have degraded trust in health authorities and slowed public response to the crisis. Misinformation about ineffective cures, the origins and malicious spread of COVID-19, unverified treatment discoveries, and the efficacy of face coverings have increased the difficulty of coordinating a unified public response during the crisis.

In a recent report, researchers at the Cambridge Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (CSER) in collaboration with The Alan Turing Institute and the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) workshopped an array of hypothetical crisis scenarios to investigate social and technological factors that interfere with well-informed decision-making and timely collective action in democratic societies.

Crisis scenarios

Crisis scenarios are useful tools for appraising threats and vulnerabilities to systems of information production, dissemination, and evaluation. Factors influencing how robust a society is to such threats and vulnerabilities are not always obvious when life is relatively tranquil but are often highlighted under the stress of a crisis.

CSER and Dstl workshop organisers, together with workshop participants (a diverse group of professionals interested in topics related to [mis/dis]information, information technology, and crisis response), co-developed and explored six hypothetical crisis scenarios and complex challenges:

- Global health crisis

- Character assassination

- State fake news campaign

- Economic collapse

- Xenophobic ethnic cleansing

- Epistemic babble, where the ability for the general population to tell the difference between truth and fiction (presented as truth) is lost

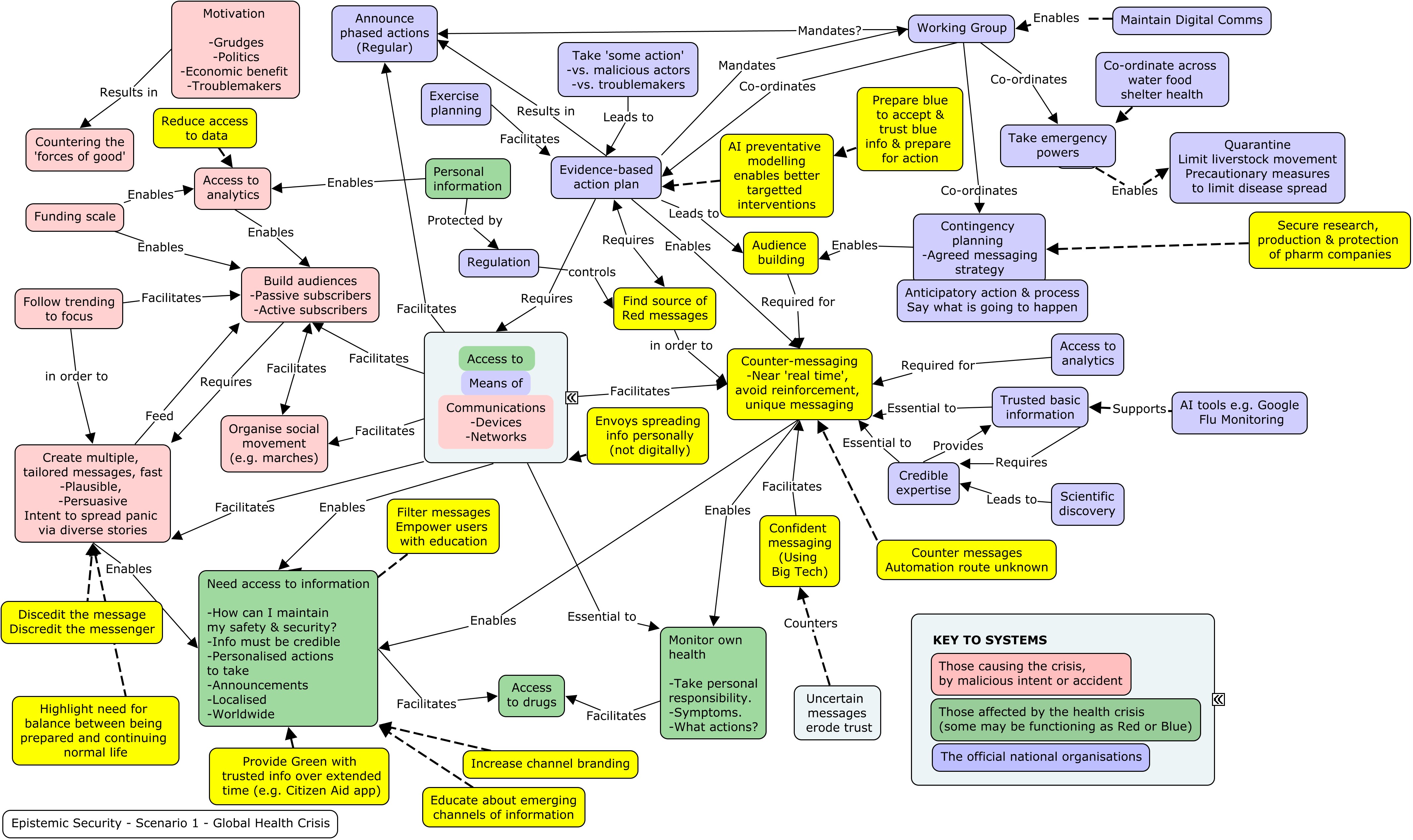

We analysed each scenario to identify various interest groups and actors, to pinpoint vulnerabilities in systems of information production and exchange, and to visualise how the system might be interfered with. We also considered interventions that could help bolster the society against threats to informed decision-making.

The systems map below is an example from workshop scenario 1: Global health crisis. The map shows how adversarial actors (red) and groups working to mitigate the crisis (blue) interact, impact each other’s actions, and influence the general public and other interest groups (green) such as those affected by the health crisis.

Systems maps help visualise vulnerabilities in both red and blue actor systems, which, in turn, helps identify areas where intervention (yellow) is possible to help mitigate the crisis.

Workshop scenario 1 – Global health crisis

(Click to enlarge image - opens in a new window)

Themes of threats and vulnerabilities

By mapping out the various crisis scenarios, several themes of threats and vulnerabilities to systems of information production, distribution, and evaluation repeatedly emerged. Many of these themes are exacerbated by the widespread use of modern communication technologies. These included:

- Modern information technologies allow adversarial actors (individuals or groups who intend to sew discord by interfering with the production and dissemination of reliable information) to more easily and widely spread [dis/mis]information which undermines informed decision-making and the coordination of collective action.

- Information abundance enabled by modern communication technologies means that the attention of information recipients is thinly spread, making it harder to ensure essential information reaches all important parties. This leads to an attention economy in which trade-offs are made by information providers between what is truthful and what is attention-grabbing.

- Insular communities that reject information that challenges their accepted views quickly emerge and persist on online social platforms. Strong in-group identity leads to greater polarisation between groups.

- Information mediating technologies like natural language processing systems and content recommendation algorithms used on social media platforms make it more difficult for users to evaluate the trustworthiness of individual information sources.

Report recommendations

The report aims to advise government actors (or other guardians of reliable information production and exchange) in preserving a society's ability to organise timely and well-informed collective action in light of the threats and vulnerabilities described above. The following recommendations are presented to highlight areas where additional research and resources will likely have a significant impact on epistemic security in democratic societies. We define an epistemically secure society as one that reliably averts threats to the processes by which reliable information is produced, distributed, acquired and assessed within the society.

1. Develop technological or institutional methods to increase the cost for adversaries in spreading unsupported, fabricated, or false information.

For example, penalties could be introduced for the knowing dissemination of false or misleading information or fines given to information organisations that do not undertake minimum fact-checking procedures.

2. Develop methods to help information consumers more easily identify trustworthy information sources.

For example, information organisations and platforms could be certified as an epistemically responsible information source. An epistemically responsible information source would be one that has done all that it practicably can to distribute true and well-founded information.

3. Explore technological or institutional methods to "signal boost" reliable decision-relevant information in an asymmetric manner.

Various professional communities have long been concerned with issues related to the production and evaluation of true information. It is possible to draw on practices employed by these communities such as scientific replication, journalistic fact-checking, legal evidential thresholds, and analytical quality assurance to boost the prevalence and visibility of reliable decision-relevant information. It is important to note that signal boosting reliable decision-relevant information requires engaging head-on with the various societally held views on what makes information true and useful, and developing and adapting tools and methods that work for, within, and across diverse communities.

4. Develop technological or institutional methods to monitor changes in social information systems to rapidly detect adversarial action during times of tension or crises.

Intervening in information systems is fraught with unintended consequences. Strategies should be developed for monitoring emerging information technologies and platforms, forecasting their impact on informed collective action, and monitoring emerging claims and narratives that could undermine collective action in times of crises.

5. Build capacity to use holistic systems-mapping procedures (constructing an integrated view of social epistemic systems) and red-teaming strategies (deliberately exploring a scenario from an adversary's perspective) to help identify and analyse threats.

Holistic overviews of social epistemic infrastructures are important because complex information systems most often suffer from multiple overlapping threats and vulnerabilities. A solution to one might exacerbate another, and many interventions will have second-, third-, and higher-level effects. Therefore, threats and vulnerabilities to socio-technical systems or information production and dissemination should not be addressed as a list of independent problems with prescribed fixes.

6. Establish working relationships with a diverse array of experts experienced in identifying and analysing threats and who could serve as advisors before and during crises.

In a crisis it is important that a democratic society can deploy people skilled in the kinds of techniques for appraising epistemic threats and vulnerabilities described in this report. These experts are currently distributed throughout various disciplines and professions (government and non-government) and employ different strategies for identifying and dealing with epistemic threats. For example, responsible journalists and journalism agencies undertake internal fact checking procedures to counter the spread of misinformation, and psychologists investigate vulnerabilities in the processes by which individuals choose to consume information and form beliefs. To address the wide variety of epistemic threats and vulnerabilities that face a heterogeneous society it is important to draw on a diversity of viewpoints when assembling a community of epistemic security experts.

7. Invest in building and curating multidisciplinary research groups and expert networks.

Epistemic security experts are embedded within separate and diverse professions and often have limited capacity to respond to (or pre-emptively mitigate) epistemic threats. We recommend establishing dedicated programs and institutions to train additional epistemic security experts and to bring together a diverse selection of epistemic security experts previously trained in other disciplines.

Towards greater resilience

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and the upcoming 2020 US presidential elections the need for robust and reliable systems of information production and dissemination is clear. Given the dispersed nature of democratic processes, the capacities for timely decision-making and collective action are easily undermined by disrupting the processes by which information is gathered, distributed, and assessed by decision-making bodies and by the public. If there is no shared belief among the actors in a community about the nature of a crisis or the efficacy of a proposed response, collective action is less likely to ensue.

Citizens of contemporary, technologically rich societies have greater access to information than at any point in history. However, information abundance and other challenges exacerbated by modern information technologies make it difficult for information recipients to evaluate the quality of that information they consume. While it is unlikely the contents of this report approach a solution to managing infodemics such as that which has slowed the response to COVID-19, we hope that the recommendations we present for the promotion of epistemically secure democracies will help us be more resilient to similar events in the future.

Related research areas

View all research areasRelated resources

-

Tackling threats to informed decision-making in democratic societies: Promoting epistemic security in a technologically-advanced world

Report by Elizabeth Seger, Shahar Avin, Gavin Pearson, Mark Briers, Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh, Helena Bacon